Right Side Capital Management: A New Take on Angel Investing

Friday, October 21, 2011 at 3:05PM

Friday, October 21, 2011 at 3:05PM Recently launched Right Side Capital Management is taking an entirely new, and in some ways radical, approach to angel and seed investing. The firm is aiming to allow startups to simply apply online for funding and receive an instant valuation and investment terms – without any pitch or in-person meeting. Companies would be initially screened by their responses to a handful of questions on two very simple forms. One form simply asks for resume-related information about the startup’s founders (things like education, management experience and technical expertise). The other form asks for information on the startup such as the industry, progress to date and financial information. Apparently the valuation algorithm they have developed will be able to provide “accurate results” for startups ranging from the idea to initial revenue stage that have raised less than $100,000 and are seeking a funding round of less than $500,000.

After the short forms are complete, Right Side Capital will invite select teams to complete long versions of the forms and submit a business plan, budget and other documents. Right Side expects to fund 25 to 50 percent of companies that make it through this stage and receive funding. In total, the firm expects to fund “hundreds” of startups per year. After funding a company, Right Side acknowledges that it cannot provide intensive one-on-one support but will provide access to incubators and other angles. In the long-run it plans on establishing an internal advisory board of experts across operational and technical areas.

Even though the firm is new, Right Side is clearly serious about early stage investing; in fact they were part of a syndicate that recently provided $24 million in funding to TechStars startups (alongside firms such as Foundry Group, RRE Ventures and SoftBank Capital). The firm’s high-volume approach to vetting and investing in startups is definitely unique, especially for a firm that utilizes an otherwise traditional Limited Partner-backed fund structure. The jury is clearly still out on the model because it’s so new and radical, but given what we know so far, I was able to see a number of positive and negatives as well. I also have some thoughts on the implications and questions for the future.

The Good:

Right Side makes it extremely easy for startups to apply for funding. It can be daunting and confusing for startups to have to figure out how to begin their search for funding and what type of valuation to expect. Right Side would be an easy, risk-free place to start - if nothing at least startups gain a reference point on a valuation to build on.

No fees. This used to be a bigger problem than I think it is now, but its worth mentioning that Right Side does not employ a “pay to pitch” model – applying is completely free. I think this is a must have feature if they want the platform to succeed, but credit to them on resisting any temptation.

Support in areas such as marketing, finance and fundraising will eventually be provided by Right Side though an advisory board. This might be more beneficial than a traditional angel investment which might only provide one line of expertise. It’s not quite an incubator model, but you might eventually have many of the benefits incubators provide.

No Board seat requirement. This is typical of most angel investments but it’s good to know Right Side will not push for a board seat. It gives startups a higher level of autonomy.

Focused approach. Right side is targeting specific characteristics which it presumably would not stray from because of the screening process/algorithm in place. We won’t know until some deal start being made but at least they will resist temptation to stray from their guidelines, something LPs might appreciate too.

The Bad:

No in-person meeting. Managing Director Kevin Dick has said that no in-person interviews will be conducted “because they don’t contribute to better investment decisions.” Sure there is some truth to that statement (not all founders will be great interviewers), but isn’t so much of a startup’s success dependent on the drive and passion of the founders? How well can these factors be gauged without meeting a founder in person? Venture investors often say that they would rather back an “A” entrepreneur with a “B” idea versus a “B” entrepreneur with an “A” idea. It has to be near impossible to gauge the drive of an entrepreneur via an application and I think Right Side has the potential to miss out on excellent opportunities.

Valuation is formula based. Whatever their valuation tool spits out becomes the starting point for negotiations. Determining the valuation for a seed round is very unscientific by nature because there usually is little to no cash flow. Usually, both sides, the entrepreneurs and investors, will have some insight that goes into a proposed valuation that isn’t captured via a metric or on an application. Sure, you are eliminating emotion at some levels, but at the same time, there might be something very valuable that might not be captured in the application form and therefore would not be compensated for in the valuation.

A significant cash investment would be required by founders. Right Side says that they want to make sure founders also take “substantial risk.” They are asking founders “to take at least a 50% pay cut compared to what they could make on the open market and put up a cash investment that is significant relative to their financial means.” I understand the need to align interests and the 50% pay cut is completely understandable for a startup. However, I wonder if Right Side loses any potential investments because founders don’t have much cash to put up. I know other angels would also require an investment by the founder, but Right Side screens for the amounts through their application without perhaps a full picture of each founder’s personal situation.

Implications:

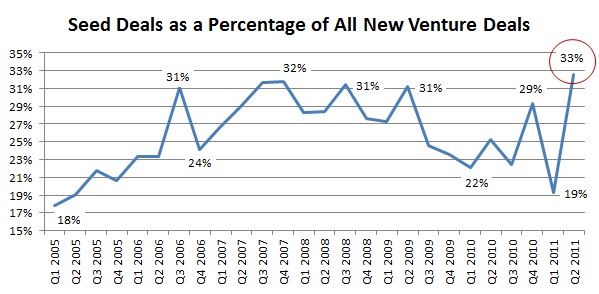

I know a lot of people are probably thinking that if there was ever a sign of froth in the angel/seed market this might be it. After all, Right Side plans on funding hundreds of startups each year without even meeting most of the founders in person. It’s almost like a controlled, repeatable “spray and pray” model. The term “spray and pray” might sound like harsh criticism, but it’s not meant to be. Fundamentally, chances of a startup succeeding and reaching massive scale are slim, therefore you have to make lots of bets if you hope to eventually back a winner. I like to think of Right Side’s model more as reverse crowdfunding - instead of lots of people funding one idea, you have lots of ideas coming into one funding source.

Right Side’s model seems very intriguing to me and if successful, has the potential to shake up the industry. But we won’t know if the model works or not till it’s actually implemented. There are also some unanswered questions – like how much ownership would they ask for, exactly what rights will they ask for (preferred, first refusal, dilution protection, etc.) and will they be able to participate in follow-on rounds (you figure continuing to back winners is where they would best be able to achieve the most returns ). We also don’t know who the limited partners are or will be. I think it would be hard to convince traditional LPs to invest in a Right Side fund, especially the first time around. I wonder if other angles might be interested as a way to more easily diversify. Or perhaps venture firms might see participating as an LP as an opportunity to access more qualified deal flow. No matter how it shakes out, Right Side’s new approach will be interesting to watch in action. We’ll just have to wait a while though - they plan on making their first invesments in Q2 of 2012.

AV | |

AV | |